Paul and Brett's Alpha

Apocryphal tales of egregious exuberance and pettifogging pessimism

As previously alluded to in the ‘wider market’ section of this monthly missive, investors are living in the age of the meme. It is not just AI as a theme and Tech stocks in particular that are wagging the dog though. We have our own corpulent meme in the shape of obesity drugs. Its impact on investor returns is worthy of more than a few words in its own right.

Unless you have spent the last 30 years living as a castaway on a desert island with nary a volleyball for company, one cannot be unaware that obesity is a significant independent risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality across a spectrum of serious medical conditions: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, most common forms of cancer, osteoarthritis, liver disease, kidney disease, sleep apnoea, and depression.

Consequentially, the increasing prevalence of obesity is one of the primary drivers of increased all-cause mortality risk in the general population and arguably the main driver of the curve separation between lifespan and years of life lived in good health (as discussed in our April factsheet).

Simply put, westerners are, in general, too fat and the rest of the world is sadly catching up rapidly, with attendant consequences for health, lifespan and the economy. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that the annual direct medical costs associated with obesity in the United States alone are $173 billion per year. The indirect costs will be multiples of this.

It is thus understandable that investors are excited about the potential for an effective anti-obesity agent; with one in three people in Western markets overweight or obese, a significant vanity component and the undeniable health benefits of people being slimmer, what’s not to like about this idea?

This is also a cycle that has played out several times before: fen-phen in the early 1990s, orlistat in the 2000s and rimonobant (2008). In all cases, side effects were highly problematic and efficacy much more limited than GLP-1s. For us old lags who remember, the hype at the time was palpable and the sales forecasts were always multi-billion dollar (and wrong).

Even so, the cadence of Wegovy’s US launch since 2021 caught everyone by surprise – Novo Nordisk literally cannot make enough of the stuff to keep up with demand. For now, Wegovy remains the only approved GLP-1 formulation for weight loss; Lilly’s Mounjaro is expected to be approved for obesity treatment within the next few months, but already has supply constraints (probably due to off-label usage in obesity).

Since launch in mid-2021, Bloomberg’s consensus expectations for Wegovy sales in 2024 have tripled to $8 billion (range $6-10bn). Consensus expectations for Monjaro sales in 2024 currently stand at $7bn (range $6-11bn) and have doubled since mid-2021. Given the background outlined above, this commercial outlook seems perfectly plausible in and of itself.

Could obesity become a $100bn or even $200bn market in the next decade? Possibly. Some sell-side analysts think it will be bigger than $100bn before 2030, which we do struggle with, but there again, what investor wants to chat to the analyst with the second or third biggest forecasts? The action is in being the super-bull or the uber-bear. Everyone else becomes a bit player. This is how the sell-side “game” has worked for many a year.

However, this will not remain a two horse race and the challenge is how the market dynamics will ultimately play out. To our minds, there are three important questions. The answers to these ‘known unknowns’ will dictate the ultimate value of this marketplace, the allocation of market share within it and thus the attractiveness of any individual player and, in the fullness of time, the impact on other adjacent areas of healthcare (that is to say treatments for obesity-related conditions). Let us consider these points further.

Before we do, it is worth reminding readers that the primary mechanistic effect of GLP-1 is to suppress appetite. The GLP-1 hormone is produced naturally in the body by the stomach as it stetches; it is the body’s signal to the brain to tell you that you are full. This is why GLP-1 facilitates weight loss: because you eat less. Hunger is also a hormone-driven sensation and GLP-1 works in opposition to this hormone pathway. If you don’t feel as hungry, you don’t eat as much.

“Question 1: the market opportunity”

There are four ‘known knowns'. We know these GLP-1 targeting drugs work effectively for weight loss, we know GLP-1 agonists have secondary health benefits, and we know lots of them are in development. We also know that rebound weight gain on cessation is a significant issue, as is tolerability.

As we headed into August, the market was expecting the publication of headline data from Novo Nordisk’s SELECT study regarding the cardiovascular (CVD) benefits of Wegovy, its obesity version of the GLP-1 agonist semaglutide. If you were not living on that same desert island, it would be incredible not to expect the results of this study to be positive given the aforementioned comments on the wealth of evidence of obesity as a CVD risk in its own right.

Furthermore, we already have additional data from CV outcomes studies of GLP-1 drugs in diabetes patients showing CVD benefits independent of weight loss, owing to positive mechanistic impacts on blood pressure, vascular endothelium, atherosclerosis progression, general inflammation and myocardial ischaemia. It is perfectly fair to say this class of anti-obesity agents stands apart from any that has gone before in terms of wider positive health impact. Does that make them the last word though?

This CVD benefit, alongside the synergistic effects with other anti-diabetic agents and the low risk of potentiating hypoglycaemic explains why GLP-1 is already $20bn drug class outside of obesity treatment.

With all of this having been known, the move in the share prices of Novo and Lilly during August (and the consequential impact on the benchmark) was somewhat surprising in our view, but perhaps it was driven by the emergence of the previously mentioned $100 and $200 billion forecasts . It will be years before Lilly has similar data for Mounjaro but investors read across, seeing SELECT as a class effect, making it all the stranger to us that its success was not already assumed.

What could prevent these heady figures being attained? There are three main drawbacks to GLP-1 as an obesity treatment. The first is tolerability, the second (and related point) is persistence of effect and rebound weight gain, and the third relates to side effects.

This class of agents has been around since 2005, when Lilly launched the twice daily GLP-1 injection exenatide. Significant strides on tolerability have been made with daily, then weekly shots and gradual dose titration that has greatly improved immediate tolerability, reducing nausea and vomiting (the primary side effects driving initial discontinuations).

Even so, it is noteworthy with today’s weekly shots that discontinuation rates are still significant at even the low initial doses. Some patients it seems are very sensitive to GLP-1 and, broadly speaking, clinical trials show 1 in 5 to one in 10 patients will stop therapy within the first year and up to a quarter will have stopped within two years.

Real-world data is, unsurprisingly, less compelling. A retrospective cohort study of 590 patients published in 2022 in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) among type-2 diabetic patients using GLP-1, based on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, which covers 13 million patients in the UK.

This study found only a minority of patients (33% at 12 months and 44% at two years) achieved ≥5% weight loss, lower than that observed in clinical trials. 35% of the cohort had discontinued therapy within 12 months and 41% within two years (higher than in comparable trials). Admittedly, some of these patients were on the daily rather than the weekly formulations, but this was not a significant factor in the rate of discontinuation.

Why are real-world results worse? Trials include ongoing support that has been shown to encourage people to stay on therapy and maintain “lifestyle interventions” that would facilitate weight loss on their own; this is why the placebo arms of these studies also show weight loss. When this is no longer available, therapy’s persistence and efficacy are inevitably compromised.

What happens if and when you do discontinue? Novo’s STEP-1 trial follow up showed that one year after withdrawal from therapy and active support, participants regained two‐thirds of their prior weight loss, with similar negative changes in cardiometabolic parameters. Anecdotal reports and our personal discussions with obesity specialists prescribing these drugs for weight loss suggest worse outcomes are often experienced.

Loss of appetite means protein intake is also impacted, and lean muscle mass is lost (albeit at a much lower rate than fat mass). Patients can end up fatter than before as they find a greater impact on activities of daily living with regained fat mass but lower muscle strength, increasing the risk of inactivity. In order to remain effective, these need to be chronic use medications.

This latter question raises further uncertainties in and of itself. Most of the studies of these agents have been relatively short-term (a few years) but patients will have to take them for decades. We now have patient registry data going back 20 or so years and so it will be possible to begin to assess the risks around chronic long-term therapy in the coming years, but we simply do not know if there are emergent risks around pancreatic health, for example.

In summary then, we can say that the GLP-1 class of agents are the safest and most effective anti-obesity agents that we have seen so far. They are not perfect though, proving less effective for some, intolerable to many and requiring lifelong adherence to maintain their benefits.

What we can say for sure at this point is that many patients will try them and, given all the press interest and current supply constraints, there is likely to be many months of pent-up demand out there in the market. However, in order for their commercial and health outcomes potential to be realised, patients need to stay on them long-term and the extent to which they are willing to do this (financially and tolerability-wise) remains highly uncertain in our view.

“Question 2: The competitive environment”

A number of sell-side firms have databases of clinical projects and there are now >100 molecules in development for obesity, many of which target the incretin hormone system (of which GLP-1 is a part). Some of these potentially promise significantly faster or greater weight loss, possibly improved tolerability through multi-modal action and more convenient oral dosing. There is no certainty that any of these will work (cf. Pfizer’s promising-looking oral GLP-1 agonist lotiglipron, which was discontinued in June), but the race is on.

Oral dosing would clearly be a huge advantage and it is much easier to scale production of a small molecule than a synthetic peptide to meet demand. Tolerability would also be an advantage and we think a multi-model approach targeting more than one hormone pathway could offer significant benefits on the tolerability front.

The desirability of faster or greater weight loss is more questionable in our view. Is the rate of weight loss the most desirable property, given a patient is going to need to stay on these drugs for life? Surely tolerability is the more relevant attribute, since side effects are a significant reason for discontinuation.

We also think that a gentler effect would help to preserve lean muscle mass, whereas a further reduction in protein intake due to greater appetite suppression would not be desirable. That said, a more potent drug might allow lower effective dosing and in this way increase the proportion of patients who can stay on therapy long-term or who achieve clinically meaningful weight loss (i.e. >5% of body mass).

Lilly and Novo are also developing next generation products: Novo has the dual acting weekly injection CagriSema and Lilly has both an oral GLP-1 agonist orforglipron and a combination product retatrutide. Should the market really presume this largely remains a duopoly between these two behemoths? If we look at early clinical data, one could argue that Altimmune, Alkermes, Amgen and Zealand all have injectable drugs in development with potential Wegovy-like efficacy.

Even if someone does not crack the holy grails of oral dosing, better tolerability or wider effectiveness, there is an interesting financial question around the impact of competition. If you are the third or fourth player to market, and you are not offering something additional in terms of efficacy (do we even need something better than the 20% weight loss seen with these drugs?), tolerability or convenience, what is your commercial lever? Even if you are brining something incremental, with efficacy already at these levels, what is the real economic value of those additional benefits?

We think there is a significant risk this could become all about price. These drugs currently cost around $1,000 per month. That is a lot for what is in effect a chronic use primary prevention product that does not permanently resolve a risk factor. If you are a late entrant, it surely makes sense to compete on price.

There is also the question of generic competition eating around the edges. Ozempic, the slightly lower dose formulation of Novo’s semaglutide used in Type 2 diabetes treatment, could see generic competition in the US by 2031. The initial doses over months 1-3 are the same for each drug, but the highest dose for Wegovy is slightly higher than for Ozempic. If one is available generically, why not use that? Ozempic will also see an IRA-mandated price cut in 2027.

“Question 3: The impact on adjacent areas”

As noted previously; obesity increases the risk of a myriad of serious long-term health complications and directly causes damage to the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems. The damage that obesity does is cumulative. If you have joint damage due to excess weight and then you lose weight, the wear and tear will slow but not reverse.

Atherosclerosis (clogging of the arteries) is not reversible either (which is important for the long-term risk of vascular dementia or stroke), nor is kidney damage. However, there will be less strain on the heart if you lose weight, so the risk of a heart attack even with established ischaemic disease may be reduced. Liver damage is potentially reversible, if it has not progressed to the fibrotic stage.

Obesity is associated with chronic inflammation and, in turn, cancer because adipose tissue is an important endocrine organ that secretes several hormones and chemokines that can impact tumour behaviour and the tumour microenvironment. Losing weight can rapidly improve these parameters and may reduce the risk of developing cancer if weight loss is sustained, based on results from some observational studies.

However, other studies (e.g. breast cancer incidence in the Women’s Health Initiative study of post-menopausal women) do not suggest that weight loss in later life conveys material risk reduction benefits, perhaps because the ‘damage’ has been done.

If we are living in a world where more and more people are losing weight and improving their health through anti-obesity drugs, we would expect a modest decline over the long-term in the incidence and then the prevalence of certain conditions, but we think this will take many, many years to become apparent.

In this respect, we think Q2 23 was a “jump the shark” moment. We were astonished to hear people argue that rates for bariatric surgery, interventional cardiological procedures and even insulin pumps and glucose monitors were at near-term risk from the (already presumed) success of these drugs. We even saw a suggestion that the growth rate of the dialysis market should be reduced because there will be less kidney disease moving forward.

If you step back for a moment, this literally makes no sense: the number of obese patients is currently growing much faster than the number of patients on these drugs, so maybe there will be an inflection in the longer-term growth rate of these things, but is that something we need to think about today?

The madness was not confined to healthcare either, we also saw arguments to reduce exposure to alcohol stocks and restaurants because consumers will be less interested in these things if on these therapies. We are not all going to want to take them and, as noted previously, they are not a panacea for all the ills of the human condition.

Insulin pumps are used mainly by type 1 diabetic patients (around 90% of users are type 1), where insulin secretion has been completely lost due to an auto-immune reaction. If you do not receive exogenous insulin, you will die. This is an incontestable fact. How fat you are and whether or not you take a GLP-1 is neither here or there: using GLP-1 or losing excess weight may impact how much insulin you need, but not the importance of delivering it when needed – a job best done by a pump with an algorithm taking data from a continuous glucose monitor.

Undoubtedly, many prospective bariatric patients (i.e. those eligible for stomach stapling or gastric band surgeries) will try GLP-1 drugs before resorting to surgery. Here in the UK, you need to demonstrate your commitment to losing weight before you are allowed to have surgery and anaesthesia in the morbidly obese is risky, so some patients are contra-indicated due to body mass.

We do expect a transitory reduction in bariatric procedures but, over time, the rate will increase back to trend as people roll off GLP-1 or become eligible for a drug-free life after losing enough weight, perhaps having used GLP-1 drugs to facilitate the required pre-operation weight loss.

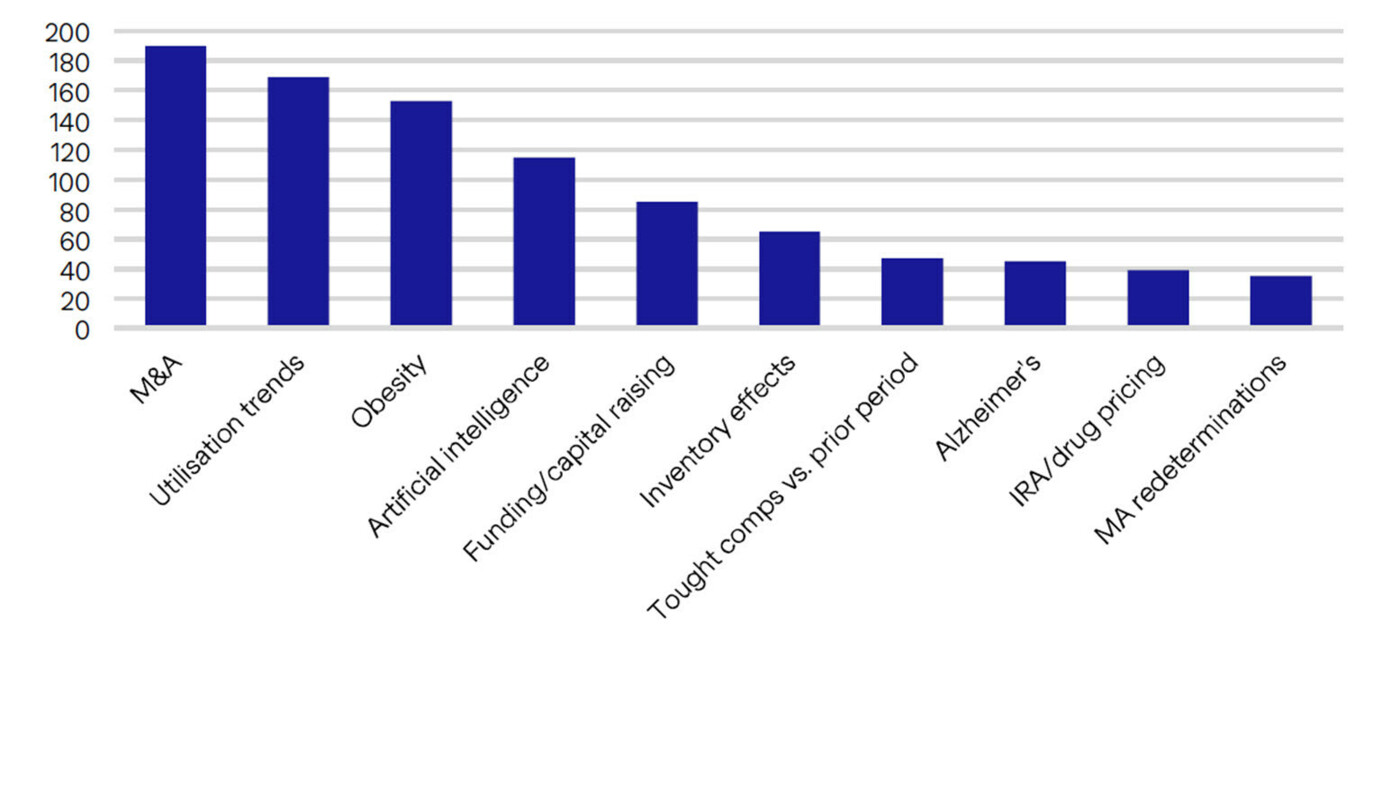

The figure below shows the most common themes mentioned on conference calls (keyword mentioned within S&P500 healthcare universe). Utilisation has been the key topic for a year now and M&A is always up there. But obesity at #3?

We would argue strongly that the healthcare world is not going to change overnight because of these drugs, but one could be forgiven for thinking that it will by the commentary surrounding us currently.

“We have no appetite for this”

Let us summarise our overall position. We do not disagree with the broad idea that tacking obesity is a compelling and potentially very substantial market opportunity within pharmaceuticals. We would also agree that the once-weekly injectable GLP-1 agonists developed by Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly are the best products developed thus far to address this opportunity, but they are no panacea.

However, there is no certainty that the dynamic between these companies will remain as it is; others may yet supersede them and pricing may yet come under significant pressure. For these reasons, we do not think that owning Novo Nordisk or Eli Lilly makes sense at 33x and 47x 2024 earnings respectively, versus an average of 15x 2024 earnings for the Bloomberg US pharmaceutical index.

Objectively, you can say that we are wrong; not being exposed to these two companies (one of which we have historically owned) has undoubtedly hurt our short-term relative performance. The year-to-date dollar total return of the MSCI World Healthcare Index stood at +1.3% as of the end of August 2023.

We have created a version of this index that excludes the GLP-1 obesity darlings Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly and then pro-rates the other index constituents accordingly. This “ex-GLP” index has delivered a comparable year-to-date total return of -2.1%, lagging the real index by 335bp.

Simply put, the healthcare fund manager’s year has largely turned on whether or not they have been over or underweight these two stocks. We have spoken with some buy side analysts where they have articulated significant internal pressure to maintain a positive view on these companies even as their valuations have doubled. We are very fortunate that Bellevue does not work in such a way and we are free to hold any opinions that we can objectively justify; there is no “firm-wide” view placed on us from above.

In the same vein, we have also been hurt by our exposure to areas such a bariatric surgery (even though is immeasurably immaterial in our portfolio), type 1 diabetes management and interventional cardiology. We have been adding to exposures in these areas and we will continue to do so because nothing has really changed at this point and we challenge anyone to prove otherwise.

We always appreciate the opportunity to interact with our investors directly and you can submit questions regarding the Trust at any time via:

shareholder_questions@bellevuehealthcaretrust.com

As ever, we will endeavour to respond in a timely fashion and we thank you for your continued support during these volatile months.

Paul Major and Brett Darke