Paul and Brett's Alpha

Losing my religion

The UK is not a meaningful healthcare marketplace in a global context; we estimate it accounts for around 2% of total spend (which is markedly below the country’s 3%+ share of global GDP). As such, what happens on this sceptred isle has little obvious impact on the wider world from a policy perspective, especially given the unique nature of how our system is organised (the single, vertically integrated, government provider model).

To be fair to it, the NHS does support a good amount of innovation within the care paradigm (the rapid evaluation of different care approaches to COVID management during the pandemic or the NHS trialling of GRAIL’s Galleri pan-cancer screening tool are good recent examples) and the UK punches well above its weight on the healthcare research side. It is a shame so many of the companies formed here (many coming out of the NHS itself) struggle for capital and end up stateside in one form or another, but that can be the subject of a future missive.

While the UK may not be a healthcare behemoth from an investment strategy perspective, it is nonetheless where the majority of our shareholders live. There is thus understandable interest in any plans to improve woeful service levels. This pejorative descriptor is not just our view: multiple polls and surveys suggest that the perception that the system is in decline is now widespread, even if the NHS still remains a source of national pride. More than half the population think the service has gotten worse in the past year, and a similar proportion expect it to have deteriorated further in 12 months’ time. Amanda Pritchard, the Chief Executive Officer of NHS England, herself recently described it as “struggling” and “damaged, but it is not destroyed”.

It is perhaps no surprise then that the state of the NHS and the state of the economy were the two biggest concerns for voters in a poll run by Ipsos in the run up to the general election being announced (immigration was #3). People want the service to be rescued/improved, but what does that look like?

Another Ipsos report, published in May and authored in conjunction with the Health Foundation (an independent charity), suggested that the public believed the service to be underfunded, along with concerns over access to care and the quality of care. Generally speaking, we Brits are a caring bunch, and surveys also suggest that staff morale and wellbeing are considered key issues (along with the perception that there are not enough staff).

So, we seem to want a better funded NHS with improved access to primary care. There seems to be a general willingness to pay more tax in order to fund improved services. Where things become a bit stickier is who should pay this extra tax (in summary – “not me” is an all-too-often heard reply).

Paving the road to Damascus

The challenges that the NHS faces are not unique to the UK, nor are they unobvious to anyone with even a modest understanding of demographics, inflation and socio-societal progress. You won’t need to look very far to find well-articulated prophecies of today’s polycrisis from three decades ago (remember the Tony Blair’s plan to ‘save’ the NHS from 2000 for instance? We’ll come back to this later on).

Moreover, let us not forget that the UK is not the United States; the civil service survives each change of government and should act as both an institutional memory and a repository of knowledge (successes and failures) to guide our future leaders when forming policy (of course, they have to be willing to listen; not an obvious strength of the political classes).

Perhaps the only thing more remarkable than successive administrations apparent inability to plan for the future, is the endless supply of healthcare rabbits that pop out of hats come general election time. Everyone has a fix, and they can make it all good within in five years.

This will surprise no one at all, but life simply does not work this way and long-term planning is needed to turn the supertanker that is the NHS, in the rough seas that our demographic and economic realities have created (or, as Nigel Farage blokeishly summarised last week: “we’re skint”).

One might conclude that we do not generally hold the NHS itself responsible for much of that which ails it, and this would be a broadly fair conclusion. It can only operate within the financial parameters and political priorities set from above. An ever-changing smorgasbord of targets is unhelpful, as is too much top-down control. One does not need to be a genius to understand that what works for primary care in Jordans is not going to fare so well in Jaywick.

With a general election fast approaching, we thought this month that we would summarise and analyse the three leading parties manifesto pledges regarding improving the provision of healthcare and social care in the UK. We have chosen to list them in chronological order of publication. Before we do so, it is probably worth listing a few statistics for readers so that they can contextualise some of the claims being made and also appreciate the scale of the enterprise that politicians like to kick about as if it were a toy to bedazzle a wan electorate (note: the below excludes social care provision and spending and not all the staff will be working full time):

NHS England employs 1.5 million people and has an operating budget for 2024/25 of £165 billion. 785,000 (i.e. half) the staff are professionally qualified clinicians and, within this, there are ~150,000 doctors and > 420,000 nurses, 21,000 paramedics and 100,000 scientific and technical staff (labs etc.). It performs over 10 million operations across > 3,000 theatres every year and carries out over 350 million primary care appointments (50 million more than pre-pandemic 2019). There are >23 million A&E visits per annum and it diagnoses around 400,000 cases of cancer annually.

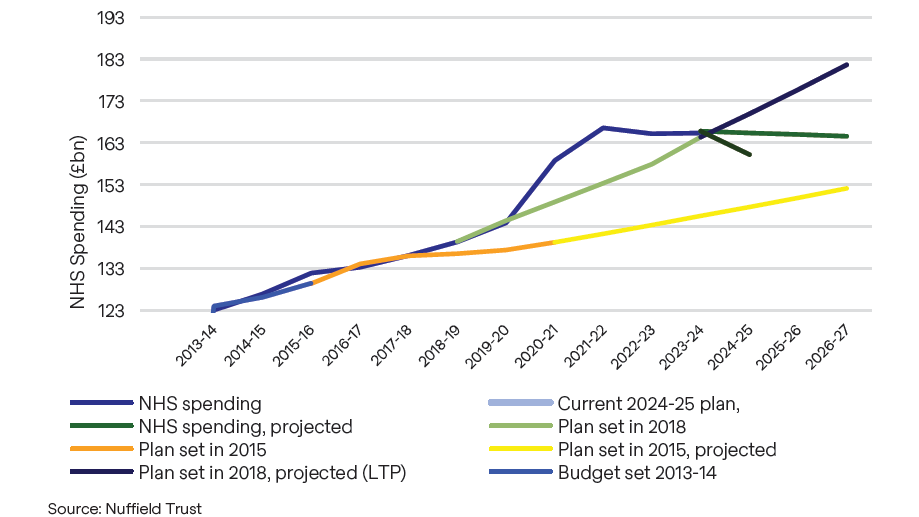

The second point that we would make is in regard to budgeting. Successive governments haven’t been very good at projecting future health spending. Figure 6 below is a little busy but nicely illustrates how the trajectory of spending envisaged for the coming decade in 2015 was dramatically revised upward in 2018 and is likely to fall well short in 2025+, since the proposed increases under the long-term plan of 2018 need to be adjusted for inflation in the subsequent years and thus current plans effectively represent a real-terms cut in planned expenditure.

To put some numbers to this, the planned 2027 expenditure of £170 billion under the 2018 long-term plan would need to be £190 billion in today’s money to account for inflation. Whatever the politicians come up with will be wrong (too low) and it will creep upwards year on year. If it does not, then services will decline rather than improve.

In our opinion, some realism in budgeting (and the tax and spending trade-offs therein) would be a refreshing addition to the political discourse. It is also worth reiterating that all the parties commended and supported the NHS long-term plan when it was published in 2019. Since it is a 10-year plan, one might therefore reasonably expect all of them to commit to funding it in real terms today.

The Liberal Democrats

Someone had to be first and it was the Liberal Democrats, whose manifesto was revealed on 10 June 2024. The overall manifesto is light on healthcare-related promises; there is no obvious plan for wholesale reform of the NHS implied within it. Readers can decide for themselves if this is a good or a bad thing.

On the funding side, it commits to £7bn in additional annual funding, but this is only a 4% increase on the 2024/25 base. The budget was £155bn in 2022/23 (the last actual year) and has increased at a CAGR of 3.1% over the past two years. As such, this increase is not a meaningful sum and, as illustrated previously, still represents a material real-terms shortfall versus the planned budget from 2018. This might be more spending, but it is still a worse NHS than was promised before the pandemic.

What will this additional spending supposedly bring? We think the proposed creation of an independent pay review body would result in all of this amount and more going on wage increases in short order.

However, it is proposed to pay for 8,000 new GPs (primary care doctors), enabling everyone the “right to see a GP or the most appropriate practice staff member within seven days, or within 24 hours if they urgently need to” and;

“to guarantee access to an NHS dentist for everyone needing urgent and emergency care by bringing dentists back to the NHS from the private sector by fixing the broken NHS dental contract and using flexible commissioning to meet patient needs”.

They also hope to address the mental health crisis by pre-emptively identifying at risk individuals in community settings (e.g. mental health workers in schools).

Firstly, let us consider the 8,000 new GPs. As noted previously, there are some 420,000 doctors in the NHS. You need to have trained as a doctor before going on to specialist training to become a GP. For various reasons, doctors are not electing to do this at the moment at a rate that is commensurate with rising demand and the replacement of retiring staff. This is not per se because we do not have enough doctors overall. Figure 7 below shows overall staff data for NHS England.

The chart shows a compound annual growth rate of 2% per annum overall and 3% p.a. for doctor numbers since the Conservative-led coalition of 2010 took power. Indeed, the NHS has added 7,500 ‘new’ doctors in the past 12 months, so pledges to add a further 8,000 of one sort or another during the next five-year election cycle may seem essentially meaningless in terms of capacity overall. The majority of the net additions have been in the higher grades (consultant, specialist) too.

Of course, we are not talking about the overall system, we are talking about primary care. According to the British Medical Association, there are c37,000 qualified GPs working in the country. Some of these work part-time, so the “FTE equivalence” number is 27,600. As such, a rise of 8,000 would represent a 29% increase in GP capacity.

By the way, that current FTE equivalent number is actually lower than it was in 2016, but there are some 40,000 more nurse practitioners in GP clinics than was the case back then. The nature of primary care service delivery has changed profoundly over the past eight years.

Does the maths add up? The NHS has a jobs portal, so you can scan for open vacancies and look at salaries. Based on this, we think that a costed figure of £150,000 per FTE is conservative, but let’s use it for simple maths; it would cost £1.2 billion per annum.

Would it make a difference to the public? GP numbers have risen by 10% since the pandemic and more remote prescribing and nurse practitioner led appointments should have freed up yet more capacity. As noted previously, NHS England delivered 50m more primary care appointments (i.e. +20%) in 2023 than in 2019.

However, the public believes it has gotten harder not easier to see a family doctor (which is true in the sense of being in an actual room with an actual GP), in part because our demographic pressures mean that appointment demand is rising faster than capacity is being added.

Given these facts, unless the Lib Dem proposal could be implemented very rapidly, it seems doubtful to us that the public would notice the difference and thus the other, related pledges about GP waiting times etc. feel to us as unlikely to be met.

Is it possible to find and train these people? This sort of proposal is not a new idea (is anything new in politics these days?). In 2020, the Conservatives committed to adding 6,000 GPs by 2024. However, even as the number of doctors practising in the UK has risen by 24,000 over the period since this announcement, the number of GPs practising has risen by ~2,750. The aforementioned NHS jobs portal currently has 1,600 open vacancies for GPs.

One can thus conclude that there are not enough people interested in the job (presumably for a variety of reasons) and, even if there were, the system does not seem to desire this much capacity currently (2,750+1,600= 4,350), perhaps because we need to build new or bigger GP surgeries to give them somewhere to work from.

Given these points, the Liberal Democrats laudable target on GP hires is likely to be missed unless something much more fundamental changes in a way that makes being a GP more attractive as a career prospect for younger doctors, and the public may not feel the difference even if they do succeed (which does not mean they should not try).

What about mental health and dentistry? Mental health referrals have grown faster than appointment availability for years now. While many people attribute this to the pandemic and the ongoing disruptions to work and learning this created for many people, NHS data shows the trend line for mental health service referrals has had a similar upward trajectory since the middle of the previous decade. This is another example of a slow-moving problem that should have been addressed years ago and has now tipped over into a visible crisis.

Prevention is always better than cure and it seems obvious that early identification and intervention could help to mitigate a burgeoning mental health crisis in an at-risk individual. The other issue with mental health is the close links to a range of other health issues. Self care can suffer for people in crisis – poor diet, no exercise, substance abuse, etc.

These things on their own can lead to health complications, and those suffering with mental health problems are far less able to cope with disease management advice or medication adherence. As a consequence, they are far more likely to call paramedics and end up in A&E; resulting in higher costs and worse outcomes.

Rather like the GP issue, one of the problems with mental health services is a lack of people choosing to train in psychiatry. It’s a lot of work for what can be an incredibly stressful and frustrating job with patients who often have these issues because of chaotic lives (the link between mental health and deprivation is stark). Fixing these external factors is sadly beyond the scope of the services on offer. So again, we see a commendable pledge in the right area where it may prove challenging to deliver tangible results.

The critical role of dentistry in the apex of disease prevention is often poorly understood. Many chronic conditions (e.g. heart disease, Parkinson’s, dementia, and some lung conditions) are associated with the presence of bacteria in the diseased tissue. The interesting question is where these bacteria come from: how do they get into the blood stream? The answer is often poor dental hygiene; these same bacterial species can be found in the mouth, where they normally do little harm.

Aesthetics and pain management aside, access to dentistry should be a cornerstone of wider disease prevention in any advanced economy. The question then is why most dentists will no longer take on NHS dental work and of course the answer is that it does not pay; literally – you lose money on the work you do. For this unarguable reason, 83% of dental practices in England will not take on NHS work.

Many of those that do only see children under NHS plans, and often only the children of their private patients (this is the funnel of new patients after all and kids are generally simple to treat).

NHS England spends about £3bn on dentistry per year (including patient co-pays; each adult contributes a small amount toward the cost of each visit or procedure). Taking a rough average for age split, we estimate that the cost of supplying a dental plan to the entire UK population of 67 million would be somewhere around £10bn, or an £8bn increase in current spending.

At commercial rates, we think dentists would be more than happy to see everyone who needs or wants treatment, and if it remained free or very low cost at the point of care (like a GP appointment), then there could be tremendous value in its preventative health benefits.

However, such a fully costed plan is not what the Lib Dems are offering, nor is it what could be afforded by the planned £7bn overall budget increase, which is also expected to pay for all the other things that we have discussed.

The Conservatives

The downside of having been in power for 14 years is that any promises you make can readily be compared to your previous commitments versus actual policy outcomes. In this regard, we think that the Conservatives start this election campaign from a very negative position with respect to healthcare; the NHS long-term plan came to fruition under their (benign at the time) stewardship and they committed to supporting it.

However, they have largely failed to do so: as noted previously, current funding is well behind the aforementioned plan in real-terms funding. Surely no-one is fooled anymore by the “record investment schtick” that all governments trot out come election time. Yes, the budget grows each year (even in real terms) but the citizenry is all too familiar currently with inflation and the consequential devaluation of money.

Simply by being in power, anyone will be able to claim no-one else ever “invested” (is it really an investment if it gets spent on operational costs?) as much as they did; it is how national budgets work over time. What matters to the voter is their perception of services and facilities. Both have worsened.

Financial chicanery aside, we have already mentioned other failed initiatives such as the hiring of additional GPs and the famous “40 new hospitals” pledge that was widely debunked at the time (on the justifiable basis that it did not actually promise 40 new hospitals at all). These comments not intended as some sort of political statement, merely an objective assessment of what has been delivered over the past 14 years.

During its tenure (many prime ministers ago), the Conservatives repeatedly committed to sorting out social care provision, yet it is still a mess and unarguably a significant factor in the NHS’ operational performance (you cannot work operating theatres at capacity when c.17% of your beds are full up with people who should not be there, but cannot be discharged on their own recognisance).

On both sides of the house, successive administrations have opposed reforms with pejorative language such as “death taxes”. In his inaugural speech as Prime Minister in 2019, Johnson recommitted the Conservatives to resolving the social care issue: “We will fix the crisis in social care once and for all with a clear plan we have prepared to give every older person the dignity and security they deserve.” Nothing has really happened since, but we do recognise that the pandemic overwhelmed many of the 2019 plans that were being made.

The new manifesto unfortunately positions itself as building on what the current government describes as a successful 14 years of investment and support. It reiterates the “40 new hospitals over the next decade” from the Johnson manifesto of 2019. As of 2024, we had 10 through planning approval and some of these are not really “new”. In fact, the capital spending backlog (i.e. agreed repairs and upgrades) for the NHS has grown over the past 14 years, in part because operational overspending is often recovered from the capital budget.

There are comments about more doctors and nurses, but these ring hollow as the data shown previously illustrated how much staffing has grown anyway over these 14 years and still overall service levels have not improved relative to where we were in 2010 (cf. Kings Fund report “The rise and decline of the NHS in England, 2000-20).

Their solution to the NHS Dental issue is to force newly qualified dentists to either undertake NHS work or pay back tuition costs, but this seems akin to a ripple in a reservoir arising from a pebble being thrown in. There are similar worthy plans to the Lib Dems around mental health.

There are some comments about IT and other investments improving productivity and thus creating £35 billion of notional savings (again, the Kings Fund report is helpful in illustrating the topic of efficiency savings and the need to ‘run in order to stand still’, due to demographic pressures).

Few would be surprised to read that the NHS has found billions in efficiency and productivity savings over the past 14 years, but no-one cares about that; it’s experiential service levels that matter. These pledges remind us of comments about ‘synergies’ in press releases for corporate mergers.

You can never unpick them; both your mangers have worked in investment banking and seen how such ‘synergies’ are identified and quantified. Perhaps one of the reasons that the budget is always wrong is that such synergies are never fully realised and so should not be so readily assumed in the budgets.

Productivity improvements allow you to do more with the same number of employees. When existing resources are overwhelmed, this might help to reduce backlogs, but it won’t actually save any money. What the Conservative manifesto does not seem to offer is any incremental investment above prior budgets on the operational or capital side. It is, in essence, more of the same.

Let us talk about social care for a minute, since the Conservatives have made the most noise about it since 2010 and the Dilnot report etc. The manifesto notes that an additional £8.6bn has been pledged over the past two years and more will become available “at the next spending review”. There is a reiteration of the pledge to cap social care costs from 2025 (as a reminder this consists of a 'cap' on how much an individual has to spend on personal care costs over their lifetime, set at £86,000 and an increase the capital thresholds for means-tested social care funding to £100,000.

Local authorities are responsible for co-funding care services for adults who cannot pay themselves. In 2015–16, councils spent ~£17 billion in England on these services. Through the austerity years, local authority spending on adult social care was protected but did not grow. As such, we have seen a real terms decrease of 8%, or 13% if measured on a per adult basis due to population growth from 2010 to 2016.

Moreover, the main costs for elderly care are wages, utilities and food. As readers will know all too well themselves, the cost inflation in all of these areas has been significant in the post-pandemic period. The 2019 government introduced additional grants worth ~£5bn, but this is barely enough to keep these services running, so a further £2.8bn of grant funding has been made available for 2024. This total of £8bn in additional funding from 2019-2024 is equal to the amount suggested in a parliamentary report from 2020 and few serious analyses suggest less than an additional £2bn per annum needs to be invested in the current system to keep it going, never mid improve it.

Lest we forget, the financial viability of that system (private operators paid by the local authority) is highly questionable as it is. We think that social care needs urgent reform and the whole business model is ripe for disruptive innovation, but only if governments will address the funding and regulatory model to support such innovation.

The Labour Party

Widely perceived as the ‘next government in waiting’, the Labour Party manifesto was probably the most eagerly anticipated, especially since the leadership had been very vague in its electoral pitch up to this point, instead focusing on a more nebulous agenda of “change”, (aka ‘anything is better than five more years of the incumbent’). Going last also allows you to frame the narrative versus your challengers. Despite this theoretical advantage, anyone expecting a revolution will surely be disappointed.

Overall, our impression is that there is less dividing the three main parties on health policy than uniting them. Labour promised to cut waiting lists by increasing the number of available appointments in secondary care (referrals to a specialist, scans, treatments etc.).

Two million more “treatments” sounds great until you read on to discover that it will be delivered by encouraging staff to work more hours (NHS staff are apt for much criticism, but not working hard enough or long enough hours isn’t one that springs to our minds, and there are patient safety issues raised by longer working hours).

“Spare capacity” in the private sector will also be used to help bring down waiting lists. Surely they realise the doctors working in the private sector are the same ones they will be asking to work more hours on their NHS contracts? This seems like it might involve some double-counting to us. Moreover, those two million additional procedures need to be viewed in context of the hundreds of millions of appointments already carried out annually and the existing backlog of 7.6 million procedures (a number that has been growing since 2013).

There is a nebulous claim to train “thousands more GPs” (cf. previous comments) and yet at the same time a commitment to bring back the family doctor concept, so that you can see the same GP each time. This will surely complicate logistics and thus negatively impact capacity, which is why it was taken away in the first place.

There is a welcome acknowledgement of the need to focus on preventative care, but only nebulous ideas on how to implement this. There is of course the same level of recognition of the burden placed on both society and services by worsening levels of mental health and the importance of dentistry but again no plans for a national dental insurance scheme of the type that would encourage and support proper care for all of us outside of the private sector.

As with the Lib Dems, there is talk of repairing relations with staff and unions over pay and a wage settlement. This will be very expensive in an organisation with >700k clinical staff and in both cases appears not to have been costed. Perhaps better wages and working conditions might encourage more people to become GPs, dentists or work in mental health, thus making some of the recruitment targets more feasible. Again though, it feels like there are assumptions stacked upon assumptions in both parties’ plans.

Labour does distinguish itself on the social care front, with the creation of a ‘National Care Service’ to better co-ordinate care and it also recognises the value of enhancing care at home. No significant funding commitments back this up however, so we don’t expect it to be able to acheive very much, but a new national regulatory body might help to usher in the innovations that could revolutionise care delivered at home and virtual supervision. There have also been specific comments about reserving social care bed capacity to alleviate NHS hospital bed blocking (this approach has been successfully trialled in some NHS Trusts).

Things can only get better [if you actually spend some proper money.

Perhaps the most shocking element of all three manifestos is the lack of additional money for healthcare in absolute terms, never mind in real terms. There is something like a 0.2% CAGR difference in NHS funding between the Conservatives and Labour over the next parliament. This rises to around 0.5% between the Lib Dems and the Conservatives, but it is still a significant shortfall relative to the planned spending under the NHS long-term plan of 2018 (in inflation-adjusted terms) and also still a rate of growth in absolute spending that is redolent of the “austerity” period from 2010-2015 (and services didn’t improve during that period).

All the while spending continues to be restrained, the population will continue to rise and to age, further compounding the gap between supply and demand. The problem here is thus not only how these claimed improvements will all be paid for, but also the inevitable realisation that services are likely to continue to get worse under all three options due to them representing further cuts to funding in real terms versus pre-pandemic plans.

These are our views, based on our knowledge. We would encourage readers to look at the reviews of all three manifestos published by the Health Foundation and the Nuffield Trust, which are both renowned for their credibility and impartiality on health-related issues in the UK, but you won’t find a more optimistic take there either. To our minds, these manifesto commitments to improved services are a fever D:Ream

For all its faults, as a nation we seem to care about the NHS and want it to continue as an institution, offering cradle to grave care that is free at the point of access. However, it is in a perilous state and action needs to be taken to bring services back to levels that the electorate will be happy with.

If left alone (and funded in real terms over a reasonable time period), the organisation could probably fix itself well enough: perhaps if it were allowed to make more autonomous and regional decisions, and if the funding environment (in real terms) were clearer over longer periods, with capital plans ring-fenced.

For example, there is an enormous irony to see the NHS at the global vanguard of testing pan-cancer screening tools and yet at the same time, the country having the lowest per capita numbers of CT, MRI and PET scanning machines in the OECD. You cannot roll out mass preventative screening if you don’t have the capability to run confirmatory diagnostics!

Sadly, our take on the plans of the three main political parties is that none of them offer any bold visions or robust commitments to fix this pressured service, it is likely to continue to limp on rather than revisit former glories (whenever you think that was).

It is also naive in our view to diminish the social care elephant. Without the back pressures our broken social care system creates being addressed, we will never be able to maximise the use of the resources that we have. Labour at least gets some credit here for its National Care Service initiative.

Let us come back to Tony Blair and the Halcyon days of 2000-2010, when the NHS was last considered by many to be on a path of improvement in terms of service quality. This came about in part because of ‘a large and sustained real-terms investment’. The budget increased by 33% over five years in real terms. There was a huge amount of capital investment within this. Such a level of incremental investment was arguably only possible because of the strong economic growth going on globally during that period; any similar effort today would have to be funded through additional taxation or further expansion of the primary deficit.

The differences were so noticeable, in part because it was preceded by a period where investment was below the level that demographic pressures necessitated. In reality, all this great reform did was bring UK health spending as a proportion of GDP up to EU-average levels. This period is not as fondly remembered outside of wonky policy circles, since again the perception of service evolution over the longer term is still generally considered to be a negative one.

As we have said more than once before: at some point, we collectively need to have a very honest conversation about what we want as a society and how we are going to pay for it. If we don’t, the fate of NHS dentistry could well portend the fate of the wider service; we will go from arguments about whether it is broken to a reality where, to all intents and purposes, it no longer exists.

Some may have hoped that honest conversation was going to happen now, in the run up to this election, but it seems very unlikely that it will. In the meantime, we would recommend that your discussions with your financial advisers around future planning and investments include the assumption that your later years will require you to either have a healthcare savings account to pay for private care (e.g. orthopaedics) or private medical insurance to help cover urgent care outside of the pressured NHS sector.

You might also want to register with the one of the local private GP services currently mushrooming across the country, because we cannot see things getting better in primary care any time soon. Of course we understand that not everyone will be in a position to make such decisions or plans. We offer no comment on the rights or wrongs of any of this; merely our take on what is currently on offer in our participatory democracy.

We always appreciate the opportunity to interact with our investors directly and you can submit questions regarding the Trust at any time via:

shareholder_questions@bellevuehealthcaretrust.com

As ever, we will endeavour to respond in a timely fashion and we thank you for your continued support during these volatile months.

Paul Major and Brett Darke